"Waiting for Godot"

By Samuel Beckett, directed by Garry Hynes

Gerald W. Lynch Theater, Lincoln Center, New York

November 5, 2018

"Andy Warhol -- From A to B and Back Again"

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Opening November 12, 2018

In the mid-Twentieth Century, Samuel Beckett’s “Waiting for Godot” seemed like an end game. Two vagabonds meet daily by a tree, and hope for a deliverance that never comes. In Act One they decide to hang themselves, but can’t decide on the best method:

ESTRAGON: Use your intelligence, can’t you?

Vladimir uses his intelligence.

VLADIMIR: (finally) I remain in the dark.

Diversion arrives in the form of a master and slave, but their journey also appears to be heading nowhere. Master Pozzo torments his lackey Lucky, who babbles theological gibberish. Pozzo goes blind as they exit in Act Two. Vladimir and Estragon continue waiting.

Ireland’s Druid Theater plays “Godot” in a stylized comic manner, calling on the traditions of Commedia Dell’arte, operetta, circus and ballet. This cool rendition makes for plenty of laughs, and also leaves room for a wide range of interpretations. Looking at it through American eyes in the 21st Century, it is possible to see “Godot” not just as a philosophical drama, but as the experience of a historical epoch. Beckett wrote it in Paris in 1948-49, with Europe in ruins, its imperial age at an end. America was the new leader of the Free World, a former colony with little history or culture. Vladimir and Estragon are stranded -- a pair of muddle-crass thinkers unable to make sense of anything without guidance from above, guidance which has gone missing. "We have kept our appointment," notes Vladimir proudly. But Godot never shows. Waiting for Godot was like waiting for enlightenment from Eisenhower.

Beckett was a natural Irish aristocrat, a vagabond in Paris, shocked to his toenails by the new world order. His vision resonated with intellectuals on both sides of the pond, and justified their pessimism. But his was not the only vision of the post-war world. Here in New York, a young man from Pittsburgh found a job drawing shoes for magazine ads. He looked at the supposed cultural wasteland and saw the first fruits of a new culture, one that would reshape the world in its image.

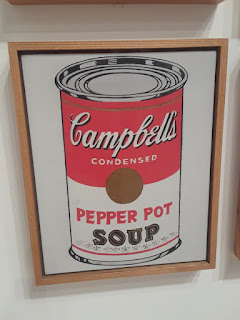

In consumer products and images from mass media, Andy Warhol located the signs, symbols and desires of our new lives, and in his prolific work showed us the contents of our own minds -- often surprising us with their revelatory beauty. In a coke bottle, a soup can, a tabloid newspaper headline, he captured both the creativity and conformity of American culture, the contradictory forces that are still with us and which shape the political battlefield today.

The Whitney Museum has filled three floors of its ample space with these artifacts and images, drawn not just from mass culture but also Warhol's more esoteric interests, one of which was dance. One of the selections on view in the third-floor movie theater is a 45-minute sequence of six silent, black-and-white dance films from the Sixties. Three are studies of dancer-choreographer Lucinda Childs. In the first she looks directly at the camera for four and a half minutes, a display of steely presence and beauty in repose. In the second she is restless, looking slightly off-camera at something of interest. The third shows only her shoulder, collarbone, upper left arm and partial chest, barely moving as she breathes.

The last two films feature Jill Johnston, feminist rebel and dance critic for the Village Voice, dancing full-out on the border of self-expression and self-parody. In a 22-minute finale, Johnston performs a pas de deux with a wet mop and an armload of household objects, then climbs a wall to balance on a toilet tank, dangling one long leg toward the bowl as the camera runs out of film -- the traditional ending for Warhol movies. The last scene is funny, but it also somehow evoked Pozzo's chilling line in "Godot" -- "we are born astride the grave."

"Waiting for Godot" runs through November 12 as part of Lincoln Center's White Light Festival. "Andy Warhol -- From A to B and Back Again" will be at the Whitney Museum until March 31, 2019.

-- Copyright 2018 by Tom Phillips

Photo of "Waiting for Godot" by Richard Termine

By Samuel Beckett, directed by Garry Hynes

Gerald W. Lynch Theater, Lincoln Center, New York

November 5, 2018

"Andy Warhol -- From A to B and Back Again"

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Opening November 12, 2018

|

| Aaron Monaghan, Marty Rea |

ESTRAGON: Use your intelligence, can’t you?

Vladimir uses his intelligence.

VLADIMIR: (finally) I remain in the dark.

Diversion arrives in the form of a master and slave, but their journey also appears to be heading nowhere. Master Pozzo torments his lackey Lucky, who babbles theological gibberish. Pozzo goes blind as they exit in Act Two. Vladimir and Estragon continue waiting.

Ireland’s Druid Theater plays “Godot” in a stylized comic manner, calling on the traditions of Commedia Dell’arte, operetta, circus and ballet. This cool rendition makes for plenty of laughs, and also leaves room for a wide range of interpretations. Looking at it through American eyes in the 21st Century, it is possible to see “Godot” not just as a philosophical drama, but as the experience of a historical epoch. Beckett wrote it in Paris in 1948-49, with Europe in ruins, its imperial age at an end. America was the new leader of the Free World, a former colony with little history or culture. Vladimir and Estragon are stranded -- a pair of muddle-crass thinkers unable to make sense of anything without guidance from above, guidance which has gone missing. "We have kept our appointment," notes Vladimir proudly. But Godot never shows. Waiting for Godot was like waiting for enlightenment from Eisenhower.

Beckett was a natural Irish aristocrat, a vagabond in Paris, shocked to his toenails by the new world order. His vision resonated with intellectuals on both sides of the pond, and justified their pessimism. But his was not the only vision of the post-war world. Here in New York, a young man from Pittsburgh found a job drawing shoes for magazine ads. He looked at the supposed cultural wasteland and saw the first fruits of a new culture, one that would reshape the world in its image.

In consumer products and images from mass media, Andy Warhol located the signs, symbols and desires of our new lives, and in his prolific work showed us the contents of our own minds -- often surprising us with their revelatory beauty. In a coke bottle, a soup can, a tabloid newspaper headline, he captured both the creativity and conformity of American culture, the contradictory forces that are still with us and which shape the political battlefield today.

| "Jill Johnston Dancing" -- film by Andy Warhol |

The last two films feature Jill Johnston, feminist rebel and dance critic for the Village Voice, dancing full-out on the border of self-expression and self-parody. In a 22-minute finale, Johnston performs a pas de deux with a wet mop and an armload of household objects, then climbs a wall to balance on a toilet tank, dangling one long leg toward the bowl as the camera runs out of film -- the traditional ending for Warhol movies. The last scene is funny, but it also somehow evoked Pozzo's chilling line in "Godot" -- "we are born astride the grave."

"Waiting for Godot" runs through November 12 as part of Lincoln Center's White Light Festival. "Andy Warhol -- From A to B and Back Again" will be at the Whitney Museum until March 31, 2019.

-- Copyright 2018 by Tom Phillips

Photo of "Waiting for Godot" by Richard Termine

No comments:

Post a Comment